BRENTWOOD, Tenn. — In general, U.S. Protestant pastors continue to stay behind the pulpit, but they may be facing unique challenges depending on their church’s denominational identity.

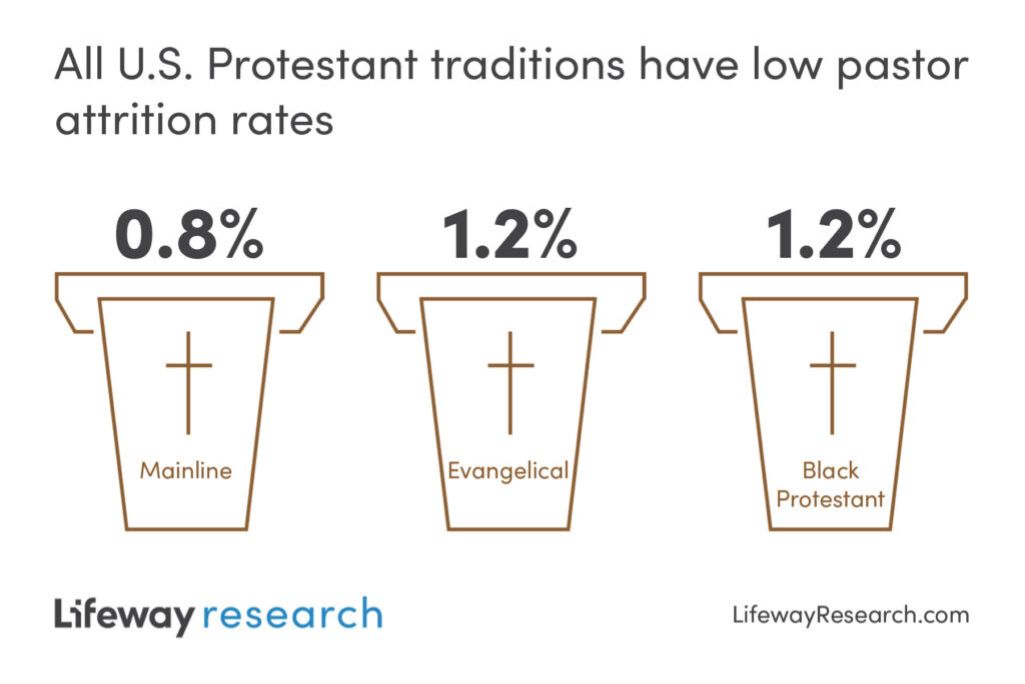

A recent Lifeway Research study of evangelical and Black Protestant pastors found the percentage who leave the ministry for reasons other than retirement or death has remained consistent over the past decade. The current attrition rate for pastors in these groups is 1.2%.

Additional Lifeway Research analysis of mainline Protestant pastors finds they also see a low percentage who leave the ministry each year — 0.8%. The combined rate for all U.S. Protestant pastors is 1.1%.

“While attrition among mainline Protestant pastors is similar to evangelical and Black Protestant pastors, there are differences in the factors around attrition,” said Scott McConnell, executive director of Lifeway Research. “Mainline pastors from 10 years ago are more likely to have retired or to be pastoring another church — often due to being reassigned to another church. Current mainline pastors are also less likely to know the history of who was pastoring their current church at the time.”

Despite similarly low attrition rates, pastors at evangelical, Black Protestant and mainline churches encounter distinctive circumstances in their respective traditions.

Mainline differences

More than other Protestant pastors, mainline clergy are more likely to have recently changed churches. They also likely have a different relationship with counseling.

Four in 5 mainline pastors (81%) began at their current congregation within the past 10 years, including 62% who have started since 2020. Additionally, 41% of mainline pastors say their current church is the first church they’ve served as senior pastor, compared to 50% of evangelicals and 61% of Black Protestants. Mainline pastors are also the least likely to feel like they can stay at their current church as long as they want (74% v. 91% of other Protestant pastors).

Still, pastors of mainline churches are less likely than pastors of other types of Protestant churches to say they often feel the demands of ministry are greater than they can handle (32% v. 47%). Perhaps relatedly, they’re also more likely to say they unplug from ministerial work and have a day of rest at least one day a week (88% v. 78%) and twice as likely as other Protestant pastors to say their church has a plan for the pastor to periodically receive a sabbatical (64% v. 32%).

“Ultimately, a pastor must be disciplined to establish a rhythm of rest, but church traditions and networks can either help or hurt those efforts,” McConnell said. “Mainline denominations appear to have been more effective at setting expectations for sabbaticals, realistic workloads and that clergy have time off each week.”

Yet, mainline pastors may be more likely to prioritize their ministries over their families. The first study gauged how pastors feel the ministry impacts their families. Pastors at mainline congregations are the least likely to say they consistently put their family first when time conflicts arise (70% v. 75% of Black Protestant and 81% of evangelical pastors).

But mainline pastors don’t feel as if they’re walking into an unknown situation when they take a leadership position at a church. They are more likely than other Protestant pastors to say their church has a document in place that clearly communicates the church’s expectations of the pastor (87% v. 72%). Mainline pastors are also more likely to say those who invited them to the new church accurately described the situation before they arrived (80% v. 68%).

Mainline pastors are less likely to say they spent personal time alone with God involving Bible study and prayer at least five times in the past week (69% v. 80%). They are also more likely to say their church would not have achieved the progress it has without them (45% v. 39%).

Among Protestant pastors who had led a previous church, mainline pastors are more likely to have said they left their last church because the congregation had unrealistic expectations of them (29% v. 17%).

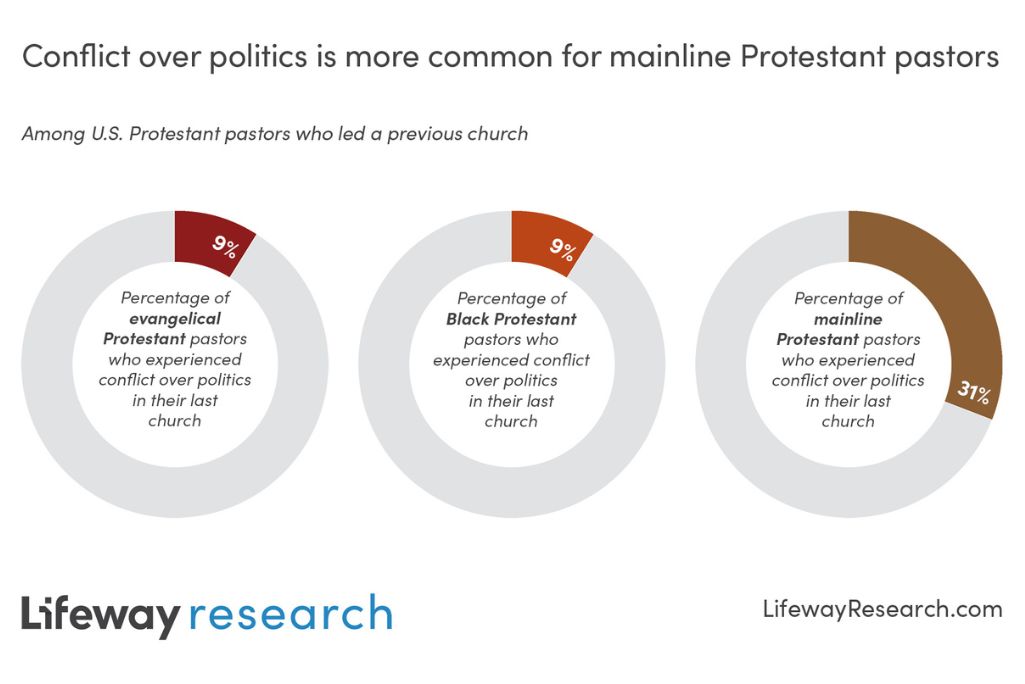

Additionally, mainline pastors experienced conflict over politics in their previous church far more than other Protestant pastors (31% v. 9%).

Earlier analysis from the study also highlighted pastoral attitudes toward and experiences with counseling. This was an area where mainline pastors differed significantly from other Protestant pastors.

Mainline pastors are less likely than other Protestant pastors to say they have another staff member present when counseling members of the opposite sex (58% v. 75%). They are the most likely to refer members to a professional counselor if the situation requires more than two sessions (86% v. 80% of Black Protestant and 71% of evangelical pastors). They are also more likely to have a list of counselors to refer people to (63% v. 52%).

Pastors of mainline churches (23%) are far more likely than other Protestant pastors (9%) to say they meet at least once a month to openly share their struggles with a counselor. They are also more likely to share with a close friend (77% v. 60%) or another pastor (75% v. 60%).

Evangelical differences

While 9 in 10 U.S. mainline and Black Protestant pastors (92%) say they consistently listen for signs of conflict in their churches, evangelicals (87%) are slightly less likely than others.

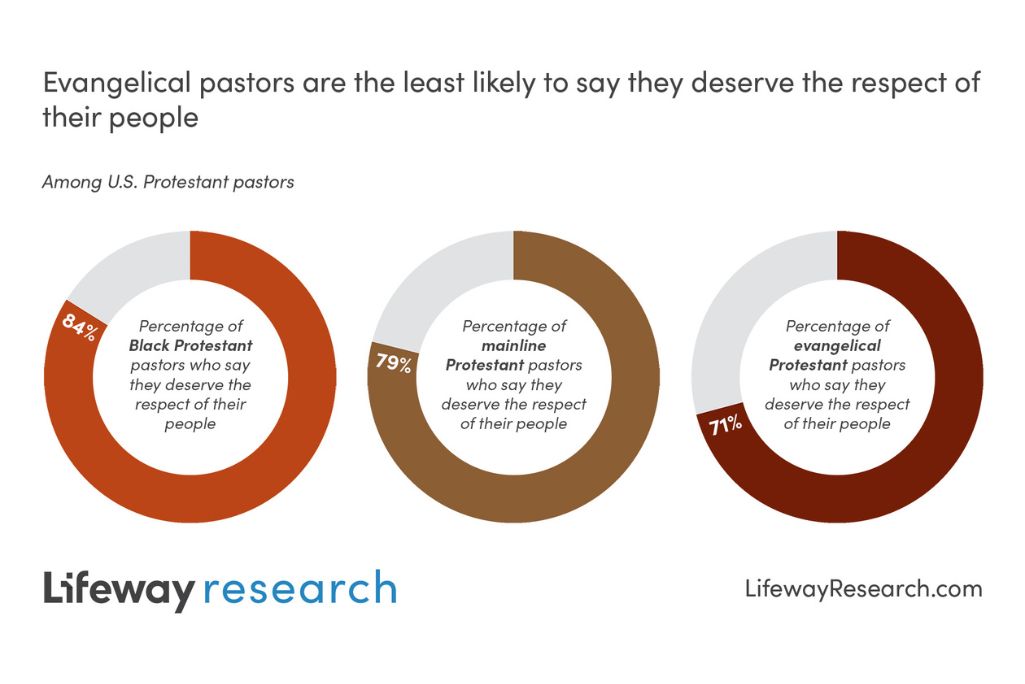

Evangelical pastors (71%) are less likely than mainline (79%) and Black Protestant pastors (84%) to say they deserve the respect of the people in their churches.

Among pastors who served at a previous church, evangelicals (11%) are less likely than Black Protestants (26%) or mainline pastors (37%) to say they left because they were reassigned. Meanwhile, evangelical pastors are more likely to have experienced conflict in their previous church over changes they proposed (38% v. 28% mainline).

In terms of counseling, evangelical pastors are less likely to refer members to a professional counselor if the situation requires more than two sessions (71% v. 80% of Black Protestant and 86% of mainline pastors). Yet, evangelicals are also less likely to have taken graduate school courses in counseling (44% v. 51% of mainline and 57% of Black Protestant pastors).

Personally, evangelicals are less likely than other Protestant pastors to say they regularly share their struggles with a close friend (59% v. 77% of mainline and 68% of Black Protestant pastors) and a mentor (40% v. 49% of mainline and 50% of Black Protestant pastors).

Evangelical pastors (90%) are more likely than mainline (85%) or Black Protestant pastors (80%) to feel their spouse is enthusiastic about life in ministry together. They are also more likely to have attended a marriage retreat or conference with their spouse this past year (24% v. 9% of mainline and 13% of Black Protestant pastors).

Black Protestant differences

Among all Protestant pastors, those at Black Protestant churches are seemingly the ones who feel the most pressure based on the expectations of their congregations.

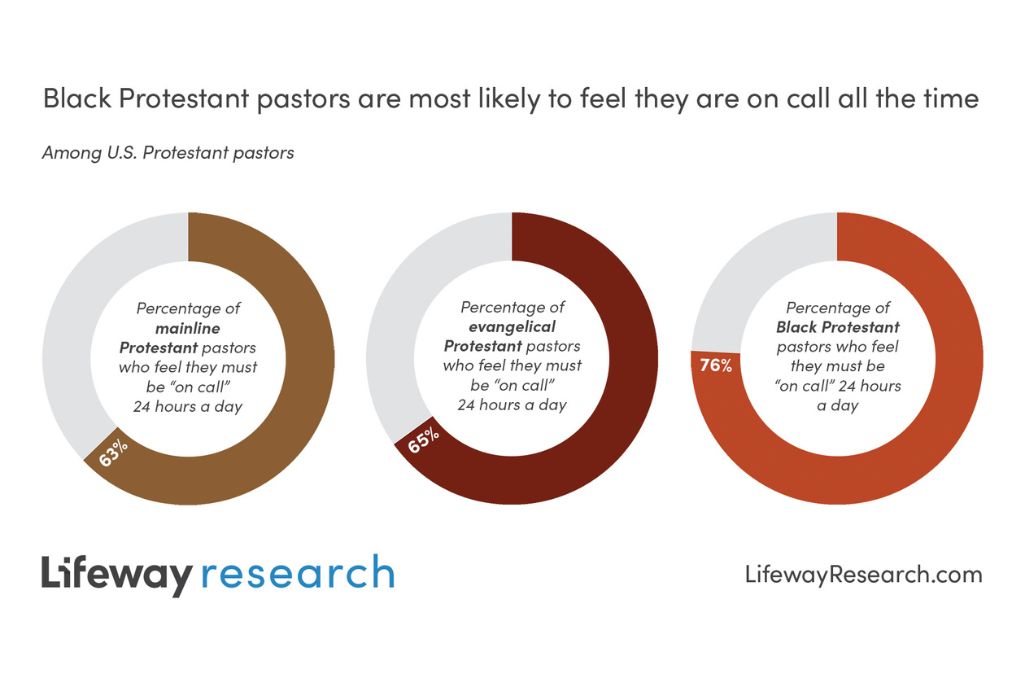

While 63% of mainline Protestant pastors feel as if they must be on call 24 hours a day, 76% of Black Protestant pastors carry that weight. Black Protestant pastors (93%) are more likely than mainline (84%) and evangelical pastors (83%) to say they work hard to protect their image as a pastor. Additionally, 19% of mainline Protestant pastors and 18% of evangelical pastors say their church has unrealistic expectations of them. Among Black Protestants, 24% say that is the case. With that, 73% of Black Protestant pastors took a vacation with their family last year, below the 82% of evangelical and 83% of mainline Protestant pastors.

Despite these differences, among pastors who previously served at another church, Black Protestants report facing fewer types of conflict than others. They are the least likely to say they experienced a significant personal attack (19% v. 35% of mainline and 37% of evangelical pastors) and conflict over expectations about the pastor’s role (14% v. 30% of mainline and 25% of evangelical pastors). Black Protestant pastors (46%) are more likely than evangelical (34%) or mainline Protestant pastors (31%) to say they didn’t experience any of the seven types of conflict asked about in the study.

“Black Protestant congregations appear less likely to impede their pastor’s leadership, though the majority still experienced conflict in their last church,” said McConnell. “It is possible the pastor’s expected presence in moments of need sows seeds of unity.”

When Black Protestant pastors leave a church, it is less likely to be because there was conflict within the congregation (17% v. 30% of mainline Protestant pastors), their family needed a change (19% v. 33% of evangelical pastors) or they were not a good fit for the church (10% v. 21% mainline). They are more likely than other Protestant pastors to have left their previous church because they felt God called them to a new opportunity (29% v. 5% of evangelicals).

For more information, view the complete report and visit LifewayResearch.com.

Methodology

The study was sponsored by Houston’s First Baptist Church and Richard Dockins, M.D. The mixed-mode survey of 387 mainline pastors and 1,516 evangelical and Black Protestant pastors was conducted April 1- May 8, 2025, using both phone and online interviews.

- Phone: The calling list was a random sample, stratified by church membership, drawn from a list of all Protestant churches except Southern Baptists.

- Online: The email list was a random sample drawn from all Southern Baptist congregations with an email address. Invitations were emailed to the pastor by Lifeway Research, followed by two reminders.

Each survey was completed by the senior pastor, minister or priest at the church contacted.

The completed mainline sample used in this report is 387 surveys. Responses were weighted by region, church size and denominational group to more accurately reflect the population. The mainline sample provides 95% confidence that the sampling error does not exceed plus or minus 5.0%. Comparisons are made within the entire Protestant sample. This sample of 1,903 surveys provides 95% confidence that the sampling error does not exceed plus or minus 2.6%. This margin of error accounts for the effect of weighting. Margins of error are higher in subgroups. Adding mainline churches to the analysis requires new weighting for all churches. Therefore, there can be minor differences between the reports. Churches are categorized as mainline, evangelical or Black Protestant based on the RELTRAD religious traditions classification.

(EDITOR’S NOTE — Aaron Earls is a writer for LifeWay Christian Resources.)