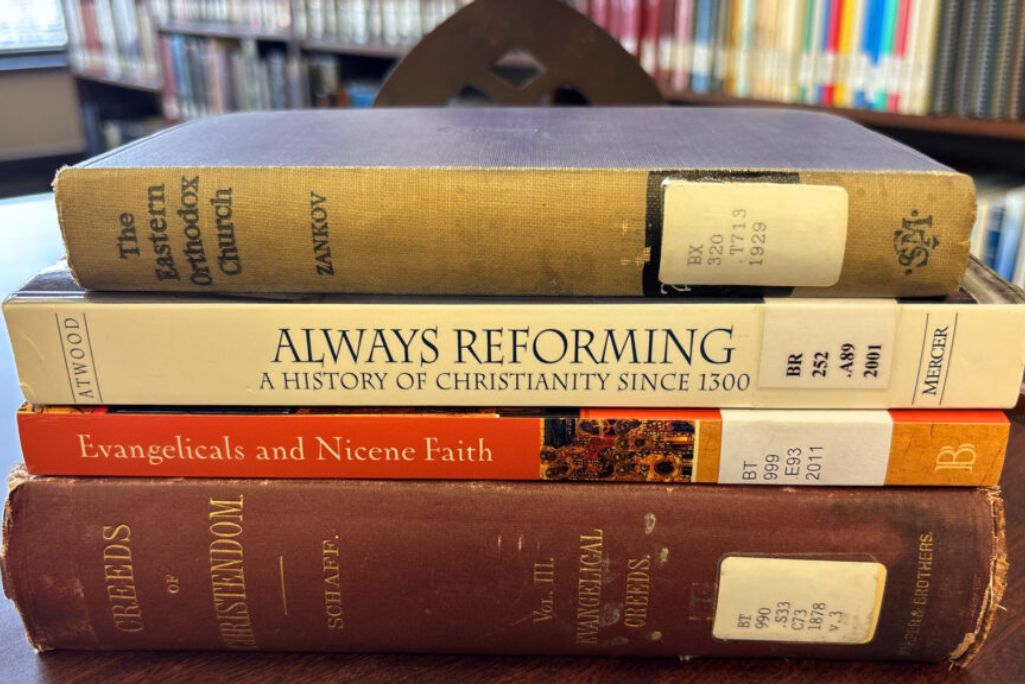

A few books on creeds, doctrine and theology from the shelves of the Southern Baptist Historical Library and Archives in Nashville.

NASHVILLE (BP) — Social media buzzed with reaction when Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary (MBTS) theology professor Matthew Barrett announced his departure from the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC) to become an Anglican. He cited the “beauty of Anglicanism” and claimed its practices better align with “how Christians have worshipped across history.”

But a cadre of Baptist theologians who focus on connecting Southern Baptists with the broader Christian tradition disagree. They say Baptist churches are fertile ground to draw from the Christian church’s theological roots — including fourth- and fifth-century formulations of the doctrines of the Trinity and the person of Christ.

Baptists must retrieve “the roots of our own tradition that extend back into the Great Tradition” of Christian theology, said Steve McKinion, professor of theology and patristic studies at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary (SEBTS). The SBC has come from “that Great Tradition. We don’t have to figure out a way to remain true to it.”

“Historic Christian tradition”

Barrett, who served eight years at Midwestern, offered three reasons for leaving the SBC in a July 24 blog post. First, he rejected Baptists’ belief in congregational church polity in favor of presbyterian and episcopal forms of church government that he claimed “are far more consistent with the whole of Acts.” Second, he rejected believer’s baptism in favor of infant baptism, citing Acts 2:39.

His third reason for leaving was that the SBC opted not to include the Nicene Creed in its confession of faith, The Baptist Faith and Message (BF&M). In response to two motions at the 2024 SBC annual meeting, the SBC Executive Committee declined to recommend the appointment of a task force to add historic confessions to the BF&M.

“I cannot stay in a denomination where the Nicene Creed has been officially rejected from inclusion,” Barrett wrote.

Barrett’s interest in the Nicene Creed relates to his participation in a debate among theologians over “eternal functional subordination of the Son” (EFS), the notion that while God the Father and God the Son are equal in essence, the eternal relations between the Father and the Son involve authority and submission. Barrett, who has joined the faculty of Trinity Anglican Seminary in Pennsylvania, rejects EFS and claims it is inconsistent with the Nicene Creed. Some Southern Baptists, led by theology professor Bruce Ware of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, advocate EFS. Southern Seminary President Albert Mohler does not hold to EFS but has argued it falls within Christian orthodoxy.

So, has the Nicene Creed been rejected in the SBC? Is the high church worship of denominations like Anglicanism and Eastern Orthodoxy more theologically rich? No, say scholars at the Center for Baptist Renewal, a think tank of Southern Baptists committed to what they call “retrieval of the Great Tradition for the renewal of Baptist faith and practice.”

“Throughout Baptist history, most of our forebears saw nothing wrong with retrieving and introducing people to the theology of the creeds and church fathers,” said Brandon Smith, cofounder of the Center for Baptist Renewal and a theology professor at Oklahoma Baptist University. “The key was: These Baptist pastors and theologians did so as committed Baptists who introduced these ideas through the lens of Baptist identity. So, what we do not need is more fear about people leaving the Baptist tradition if they read the creeds; rather, we need more committed Baptists showing people why the Christian past is part of our heritage too.”

While Southern Baptists declined to add the Nicene Creed to the BF&M, messengers to this year’s SBC annual meeting in Dallas identified themselves with the Nicene Creed in a resolution on the BF&M and the Cooperative Program.

“From our confessional beginnings,” the resolution stated, “Baptists have identified ourselves with the historic Christian tradition, especially on the doctrines concerning Christ and the Trinity as exemplified, for example, by the Nicene Creed.”

From Nicaea to Nashville

Malcolm Yarnell, a fellow at the Center for Baptist Renewal and research professor of theology at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, disagrees with Barrett’s arguments about congregationalism and baptism. He also noted that “Baptists in the Southwest have long advocated using creed to express orthodox biblical interpretation.”

Late Southwestern Seminary professor James Leo Garrett argued “the Trinitarian dogma of the early church was presumed by early Baptists,” Yarnell said. Southwestern theologians L.R. Scarbrough, W.T. Conner and B.H. Carroll all affirmed the creeds of the early church. Current professors at the seminary “regularly use the Great Tradition to defend Christianity against Jehovah’s Witnesses, Mormons and other cults.”

W.A. Criswell, a former SBC president and longtime pastor of First Baptist Church in Dallas, preached a months-long series of Wednesday sermons on confessions of faith. In that 1974 series, he affirmed the Nicene Creed and the Apostles’ Creed, among other early church confessions, as expressing the Bible’s teaching.

A 2020 book published by B&H Academic, “Baptists and the Christian Tradition,” featured essays by more than a dozen contributors arguing that Baptist faith and practice align with the Christian tradition. The book’s foreword asked, “What hath Nicaea to do with Nashville?” Plenty, it concluded.

Still, Barrett isn’t the only notable defection from low church evangelicalism to high church traditions like Anglicanism. Author and speaker Beth Moore left the SBC for Anglicanism. Former Evangelical Theological Society President Francis Beckwith left evangelicalism to become a Roman Catholic. Campus Crusade for Christ leader Peter Gillquist left evangelicalism for Eastern Orthodoxy in the 1970s, as did the son of evangelical philosopher Francis Schaeffer in the 1990s.

McKinion, who also serves as a fellow with the Center for Baptist Renewal, said he receives calls from Southern Baptists thinking about becoming Anglican. He attempts to steer them in a different direction.

“They think, ‘If I become Anglican, I will be more like the early church,’” McKinion said. But the Anglican “Book of Common Prayer” and Anglican polity were not “present in the ancient church the way they are present in the modern Anglican Church … All those aspects of practice are cultural.”

Historically, the larger migration has been from Anglicanism to Baptist churches. “The Baptist movement began with a mass migration from the Church of England,” Yarnell said, “including the first leaders of the General Baptists and the Particular Baptists.” They became convinced that believer’s baptism and congregational church government were scriptural.

Most growth in the Anglican Church in North America (ACNA), the theologically conservative denomination to which Barrett went, has come from liberal Anglican denominations rather than low church evangelicals. Nearly every ACNA diocese reported attendance increases over the past two years. In contrast, the theologically liberal Episcopal Church USA has lost nearly a third of its average worship attendance over the past decade, reporting just over 400,000 average attendance in 2023.

Michael Haykin, a church history professor at Southern Seminary and a Center for Baptist Renewal fellow, said he finds facets of Anglicanism appealing, including its liturgy. He even uses “The Book of Common Prayer” as a model for a liturgical service he leads once a month at his local Baptist church. But he remains “a confirmed Baptist.

“I am well aware that there are other traditions besides the Baptist one (that of Anglicanism, for example) that have been witnesses to the purity of New Testament (NT) doctrine,” Haykin wrote in a blog post released the same day as Barrett’s. “But I deem the Particular Baptist stream to best represent NT life and polity. And having lived and breathed that world of late Antiquity, the previous sentence is not lightly made.”

Though defections from the SBC garner attention, the movement within the convention to reconnect with the Christian tradition has gained steam. The Center for Baptist Renewal lists nearly 40 Southern Baptist fellows on its website, including Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary (SWBTS) President David Dockery.

“What it means to be Southern Baptist,” McKinion said, “is to have received within a particular context that Great Tradition.”

(EDITOR’S NOTE — David Roach is a writer in Mobile, Ala.)