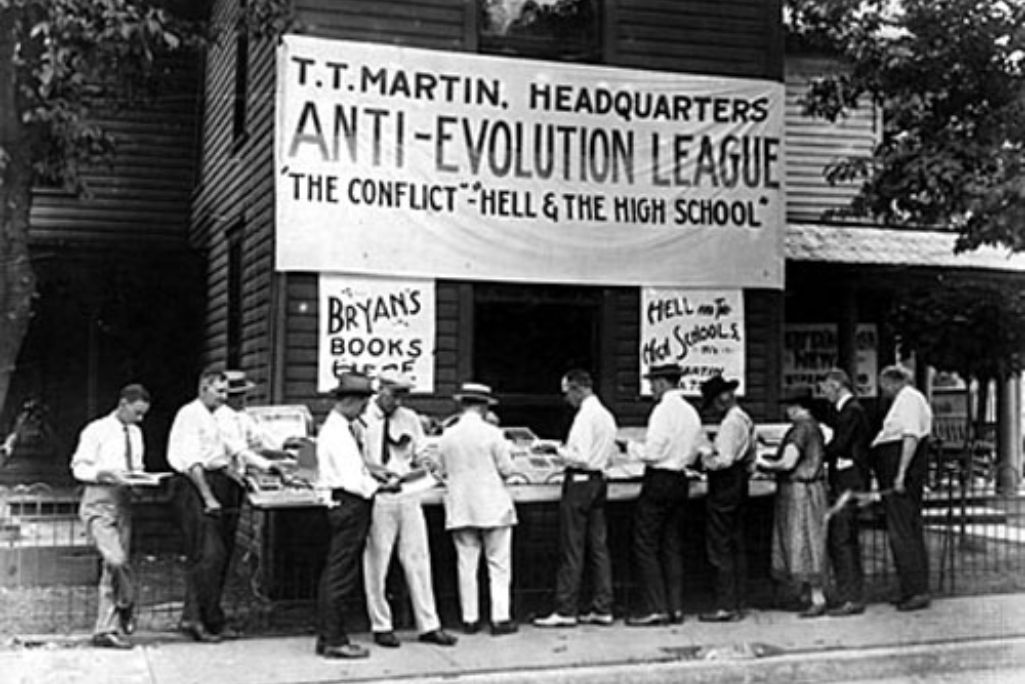

Today, a lot of Christians are thinking through the role of the church and the role of the state. Some cringe at the mere idea of Christian influence on the government. Some are looking with some nostalgia at magisterial Protestantism. But as Baptists, we don’t face a choice between secularism and theocracy.

The Founders resisted the idea of a state church. James Madison believed that “The Religion then of every man must be left to the conviction and conscience of every man; and it is the right of every man to exercise it as these may dictate.” Madison and Jefferson were influenced by Baptist pastors and theologians who insisted on the language included in the First Amendment to the Constitution, which prohibits the establishment of a state church.

The Founders, having surveyed the wreckage of the mostly unholy alliances between state and church throughout history, envisioned a new arrangement that would allow people to worship freely. Baptists had left England for that very reason. They grounded their beliefs about government in their interpretation of Scripture and the idea that Christ, not government, is Lord of the conscience.

Yet a Baptist conception of “a free church in a free state” is not the same thing as the kind of ideological secularism that many people have embraced since the middle of the 20th century. The historian and scholar Daniel L. Dreisbach was right when he wrote, “The ‘high and impregnable’ wall constructed by the modern Court has been used to inhibit religion’s ability to inform the public ethic, to deprive religious citizens of the civil liberty to participate in politics armed with ideas informed by their faith, and to infringe the right of religious communities and institutions to extend their prophetic ministries into the public square.”

Secularists’ vision of the naked public square is one banning religious authoritarians from pressing a thumb on the scales of justice. But what this belief often looks like in practice is the restriction of any interaction between the state and religious communities in ways that punish good ministry, such as food pantries, adoption agencies, prison ministries and educational institutions. One constitutional lawyer called this jurisprudence “search-and-destroy missions to obliterate all things religious from public life.”

What has often been applied is the so-called Lemon test, which originates from a 1971 Supreme Court ruling, Lemon v. Kurtzman, which broadened the First Amendment’s establishment clause beyond what the drafters of the Bill of Rights had originally intended. By this standard, the government can violate it any time it is involved in any religious endeavor that doesn’t have a secular purpose. That turned the First Amendment from a positive that prevents the government from meddling in church affairs or establishing a preferred religious practice over another to a negative that pushes any and all religious activity out of the public square.

What secularists imagine these rules will do is chase out a sort of evil Spanish Inquisition that they imagine wishes to rule the country. In practice, the major victims of such legislation are religious groups that genuinely want to work with their local or state governments to help solve real-world problems such as addiction, foster care, prisoner rehabilitation, poverty and other social ills. Under this regime, ministries must abandon the faith commitments that compelled them to do the work in the first place and are forced to adopt a “secular purpose.”

Thankfully, in the 21st century, a more originalist Supreme Court has begun to claw back the Lemon test while also maintaining the integrity of the First Amendment. Recent cases include Kennedy v. Bremerton, which allows a football coach to lead voluntary prayer; Fulton v. Philadelphia, which said that the city of Philadelphia couldn’t push evangelical and Catholic social service agencies out of the adoption and foster care process simply because they hold evangelical or Catholic beliefs; and Trinity Lutheran v. Comer, which prevented the state of Missouri from discriminating against a Lutheran school that applied for playground improvement grants offered to any institution of education.

But the social costs remain. Today religion is still often considered, especially by elites, as a quaint practice best reserved for private worship. Consider the subtle language shift by progressive politicians from defending “freedom of religion” to “freedom of worship.” The legal scholar Ashley E. Samuelson wrote, “To anyone who closely follows prominent discussion of religious freedom in the diplomatic and political arena, this linguistic shift is troubling. The reason is simple. Any person of faith knows that religious exercise is about a lot more than freedom of worship. It’s about the right to dress according to one’s religious dictates, to preach openly, to evangelize, to engage in the public square.” Consider the fact that the Obama administration tried to force the Little Sisters of the Poor to distribute abortifacients as part of their health care coverage, even though doing so would violate the tenets of their Catholic faith. Or the way it tried to force Catholic hospitals to perform abortions, even though doing so would violate the tenets of their faith. In other words, progressives argue that there are large swaths of public life in which people are not allowed to be religious.

As a result, society suffers. When the shared moral norms that once bound society together recede, what replaces them is often worse. This is not a wide-eyed nostalgia about a fictional “golden era” of America’s past. Civil religion didn’t spare Americans from sin. Even in the best of times, our grand experiment is still an experiment by fallen humans. But secularism is not a better social arrangement. And Baptists, who resist a state church, also understand that a neutral public square is fiction. This is why we engage local, state and national governments. It’s why Baptists often serve at the highest levels of government. And it’s why, while we pray for revival, we work where we can to renew our communities. Even as we await that city whose “builder and maker is God” (Hebrews 11:10).

(EDITOR’S NOTE — This article is adapted from “In Defense of Christian Patriotism” by Daniel Darling, director of the Land Center for Cultural Engagement at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary.)